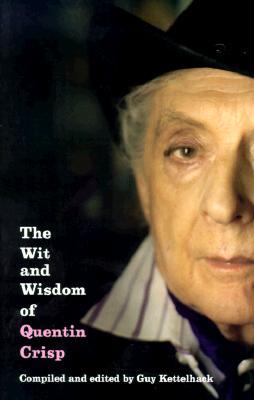

THE ENIGMA OF DENIS PRATT by Guy Kettelhack |

|

Dear Mr. Ward has disinterred and now kindly offers here for your consumption a section of a book I once worked on—not destined to see the light of day—Shadows of the King, about gay men and their fathers—in which I had the presumption to apply some Freudian notions to dear mysterious Quentin Crisp's reaction to the influence of his father.

I remember, right after I'd written it, phoning Quentin to read him this section to see what he thought of it. His response amounted to a slightly worried: "Oh dear." It was all much simpler to Quentin: he didn't get on with his father (ever), and he did get on with his mother (always), and that pretty much was that. I'm abashed now to be reminded that every time I've tried to turn Quentin into "theory," his warm presence pretty much drained of blood and fell to ash. Quentin—then and now—defies the abstract. He is and was precisely what he said of himself: like a poem, he can't be reduced. However, there may be a tiny squiggle of something in the following mostly misguided attempt to "explain" the great man, some little light. I'm happy for having gratified Quentin in at least one small way: he was grateful for any attention, even when (as here) conclusions drawn were mostly wrong. They do, perhaps, however, poke the "hive" and awaken our memories of the real breathing man. Anything that does that can't, I suspect, be all bad.  I am honored by being able to count myself as one of Quentin Crisp's friendly acquaintances (calling myself a friend would seem too presumptive an intimacy, despite the fact that I've worked with him as agent and collaborator and seen him as occasional lunchmate for fifteen years). Mr. Crisp has long startled the world with his self-honesty and acute social commentary. He offers what I consider to be an interesting example of paternal influence as well.

I am honored by being able to count myself as one of Quentin Crisp's friendly acquaintances (calling myself a friend would seem too presumptive an intimacy, despite the fact that I've worked with him as agent and collaborator and seen him as occasional lunchmate for fifteen years). Mr. Crisp has long startled the world with his self-honesty and acute social commentary. He offers what I consider to be an interesting example of paternal influence as well.Quentin Crisp freely admits that he wishes he had never been born. This, to most ears, sounds like self-hate. In fact, it isn't really: self-hate would be too passionate a self-regard. He is much cooler and more pragmatic about himself than that. Mr. Crisp has confided to me and to the world that he has always felt like a woman born into a man's body. This is not a popular idea with most gay men today—who desperately revel in, cultivate, and fetishize a glaring and unassailable "masculinity"—and indeed, it's not an idea that I feel is true about most of the gay men I know, including myself. It is, however, what Mr. Crisp believes about himself. But what interests me most is what Mr. Crisp has done in response to what he believes is the unhappy accident of his existence. He has decided to be every bit of his misconceived self anyway. He would say he had no choice but to be himself, but of course he had plenty of choice to hide who he was—the world is full of people trying to be who they are not because they think who they are is unacceptable. For whatever reasons (and I will suggest one, in a moment, that would probably appall him), hiding who he was, for Mr. Crisp, was an untenable idea. "I have thrown myself on the mercy of the world," he said once to me. "And, oh! The relief." The relief? "Yes," Quentin explained. "When you accept whatever comes your way, never initiate a single thing in your life, you cannot be held accountable. You are free." It was the only freedom Mr. Crisp could conceive for himself. He wrote his classic autobiography, The Naked Civil Servant (which he says he wanted to call I Reign In Hell), not from any burning desire to unburden his soul to the public, but because somebody asked him to—more important, offered to pay him for it. I have heard him express only one desire to do anything: he thought it might be nice to be in a film. Even this he did nothing on his own to pursue, except to say yes when the part of Dr. Frankenstein's (Sting's) assistant Igor in The Bride was offered him, and later, the part of Elizabeth I in Orlando. Otherwise, Mr. Crisp has expressed no preferences for anything: his motto is "I want what you want." He has tried, as he says, to make himself into "that wide shallow vessel into which anyone can pour his life" or, as he says of Greta Garbo, "a blank canvas onto which people paint their dreams." But Quentin Crisp had an all too real birth and upbringing in middle-class Edwardian Surrey. The familial name given him was Denis Pratt. ("Prat" is of course slang for rear end, Quentin happily reminds me.) He had siblings, as well as a mother whose influence he acknowledges, and a father whose influence he does not. Addictively drawn to such dismissals, I asked him about his father. Quentin replied: "He never laughed. He never spoke. He was just there. He ignored me and went on as if nothing unpleasant had happened." Not that Quentin lacked sympathy for him. "I now know that he had no money. He died when he ran out of it completely. I think because he didn't know what else to do." He died when Quentin was 22, which was about the time he moved to London (1930). Please, dear Quentin, forgive me for this attempt at psychoanalysis—you of all people seem to me immune to it—but might there be a connection? Two connections, even: one, the phrase with which he sums up his father—"he went on as if nothing unpleasant had happened"—is one he uses all the time to sum up himself (it's not a bad description of his whole approach to life). And the money. Quentin Crisp has assiduously held onto every shilling/cent he could from the little money he has made. Money is his God—not that he has ever lusted after great quantities of it ("it would not befit my station")—but as it is his one external requirement for survival, it is "sacred." (He believes the lack of it killed his father.) Mr. Crisp's imperturbability and extreme thriftiness seem to me two central, self-defining lessons learned at his father's unyielding knee. The father's remoteness may even find an echo in the way Quentin rarely looks into the eyes of anyone who converses with him. It seems at least plausible that his circumspect behavior coupled with his iconoclasm is both a reflection and defiance of Pater Pratt.  Quentin Crisp might be seen to have transferred this reflection and defiance to another "father:" London, to which he fled about the time his father died, freed perhaps to do so because of that death. While I have no basis to think that he acted out his own father's secret urge to be a flamboyant homosexual (Quentin would find the notion absurd), he certainly gave expression to many of Father London's repressed taboos (as Oscar Wilde had done before him). Inventing a new name (rather passively: both parts were given him, his surname by chance—something to do with having at short notice to pretend to be a "Mr. Crisp" at one of his Soho coffeebars; his first name conferred on him by the collective decision of friends) partly to protect the paternal name from notoriety, Mr. Crisp's polite English reticence and outrageous sexually ambiguous appearance bespeak the same reflection and rebellion which seem to me paternally derived: faultless in behavior, but forever taunting in his visual impact and provocative opinions. Although this ambivalent stance characterized him uncomfortably throughout his childhood, he allowed it blatantly to define him virtually from the moment his father died: by now it's (as if) set in amber. And Father London has a clear dose of envy: interest in him remains high in the U.K. partly because Quentin managed the supremely enviable trick of getting out—how did such an unlikely "son" manage the feat? An odd-looking, elderly, effeminate man with no money who prides himself on the fact that he hasn't "worked" since he crossed the Atlantic? (Father London's blood seethes with envy.) Quentin Crisp might be seen to have transferred this reflection and defiance to another "father:" London, to which he fled about the time his father died, freed perhaps to do so because of that death. While I have no basis to think that he acted out his own father's secret urge to be a flamboyant homosexual (Quentin would find the notion absurd), he certainly gave expression to many of Father London's repressed taboos (as Oscar Wilde had done before him). Inventing a new name (rather passively: both parts were given him, his surname by chance—something to do with having at short notice to pretend to be a "Mr. Crisp" at one of his Soho coffeebars; his first name conferred on him by the collective decision of friends) partly to protect the paternal name from notoriety, Mr. Crisp's polite English reticence and outrageous sexually ambiguous appearance bespeak the same reflection and rebellion which seem to me paternally derived: faultless in behavior, but forever taunting in his visual impact and provocative opinions. Although this ambivalent stance characterized him uncomfortably throughout his childhood, he allowed it blatantly to define him virtually from the moment his father died: by now it's (as if) set in amber. And Father London has a clear dose of envy: interest in him remains high in the U.K. partly because Quentin managed the supremely enviable trick of getting out—how did such an unlikely "son" manage the feat? An odd-looking, elderly, effeminate man with no money who prides himself on the fact that he hasn't "worked" since he crossed the Atlantic? (Father London's blood seethes with envy.)By reconfiguring himself—but using who he was as the only clay of that reconfiguration—Quentin Crisp resolved his Oedipal dilemma in an interesting way. While defiance of "Father" may permanently have colored his style, his stance became softer, more flexible than that. He found a way to tolerate—even exploit—his uniqueness (no easy feat when you start out wishing you'd never been born). He stood up, as it were, next to his "father," learned to co-exist with him without destroying or falsifying who Quentin was in the process. He allowed himself to be who he was and the world to be what it was. This required doing something very difficult, what I believe is the whole Oedipal aim: to accept his aloneness—and then go on (as he says) "as if nothing unpleasant had happened"—go on living (as he also says) "in spite of everything." Click Ancient, Glittering & Gay to read Guy Kettelhack's "A P.S. Reflection on Quentin Crisp." Also read Mr. Kettelhack's contribution to "A Centennial Celebration" for Quentin Crisp here |

|

|