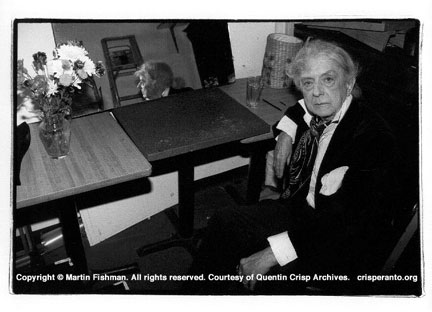

NOTES ON KNOWING QUENTIN by David McReynolds |

|

Quentin Crisp was a remarkable person, otherwise none of us, Phillip Ward, nor I, nor any of thousands of others, would still remember him. Remarkable people are "remarkable in different ways," impressing each of us differently. My own politics are "far left" (socialist, pacifist), and Quentin's, so far as I could tell, were pretty reactionary. His view of the British monarchy was appropriate for someone his age, and of his class background—respectful, taking the monarchy as a given. (He had little sympathy for Princess Diana, whom, he felt, didn't grasp the nature of the monarchy.) If he wasn't passionate about the AIDS crisis (and he wasn't), it was, again, a reflection of his age. I realize in my own case, being 75, that if I were just ten years younger I'd be dead—I was just old enough to have passed beyond the passions of back-room sex when the great gay sexual revolution burst on the New York scene. Quentin was old enough that he had almost no personal friends his own age who had died of AIDS. And he had endured a great deal in his life, which was easy to forget as you sat in the old Cooper Square cafe for lunch and chatted. A younger friend joined us once, a very politically correct fellow, who asked, in some outrage, why Quentin wasn't more publicly concerned about "gay bashing." His response was a slightly impatient "My dear, I have lived through all of that." Three things impress me as lessons for my own life, and perhaps yours. First, while Quentin was given to strong opinions artfully framed, he was almost never "catty." The kind of vindictive bitchiness that sometimes seems to afflict gay society was totally absent in the conversations I had with Quentin. Second, he went to work even when he was desperately ill. Toward the end of his life he did a show on Broadway [at the Intar Theatre on 42nd Street, produced by John Glines]—and for part of the time the show was running he was seriously ill with the flu. A lesser actor would have pleaded illness, and it would have been justified. Quentin struggled on. Third, and worth keeping in mind as you get older, "never say no when someone asks if you want to go somewhere." While Quentin would always say he had to consult "the sacred book" (his diary), it wasn't to find an excuse to decline an invitation, only to make sure he wasn't already committed. So he stayed young in outlook. I look back on all the movies we saw together and treasure those times. Good movies, good company. (And Quentin, whose mind was very sharp—he said he kept it in shape by doing crossword puzzles—never saw a film twice, yet seemed to remember every detail of the plot and the actors.) Also read his essay on Quentin Crisp: The Radical. |

|

David McReynolds, well-known peace activist for the War Resisters' League and former Presidential candidate for the Socialist Party USA, has written numerous articles in publications as diverse as the Progressive, Village Voice, WIN magazine, and Nonviolent Activist. He is the author of a collection of essays titled We Have Been Invaded by the 21st Century, published in 1969.

|