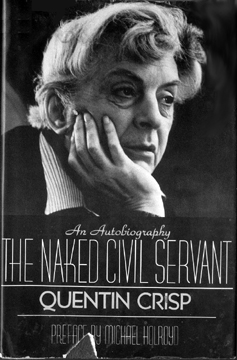

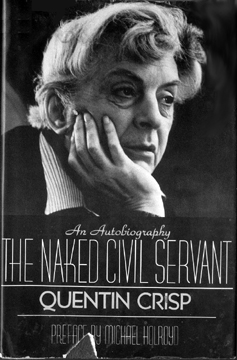

Jessica Schuman: He was reluctantly born on Christmas Day in 1908. To his dismay he found himself to be the son of middle-class, middle-brow, middling parents who lived in Sutton, a suburb of London, England. After an uneventful childhood, he was sent, between the ages of 14 and 18, to a school which was like a cross between a monastery and a prison. There he learned nothing that could be useful to in adulthood except how to bear injustice. His ignorance of everything but this and his ambiguous appearance made any career impossible, except in the arts. And this describes the early life of Quentin Crisp, also known and perhaps best known as the Naked Civil Servant. I’m Jessica Schuman, and today Quentin Crisp is my guest. Welcome.

Quentin Crisp: Thank you.

JS: You, perhaps, best exemplify Shakespeare tenet that, "the world is a stage and we but players." Your whole life, in recent years, is an acting out of who you are. Perhaps you’d talk about how you evolved who you are? How you evolved this style that you’ve become notorious for? And you’ve said that it’s certainly not famous, it is definitely notorious. Whether you dabbled in other lifestyles, whether you had other images which you donned and then threw off because they didn’t suit you, like a hat that didn’t quite fit your head.

QC: Well, I did, of course, experiment to some extent because everybody does. In the beginning I was entirely unsure of myself, especially when I was at school. And when I was young I alternately confirmed and denied my existence. But after a while you can’t keep that up. You have to make up your mind whether you are going to try and make yourself over to the world’s opinion of what you should be like, or whether you’re going to stay with what you find that you are. And what made the world cross was to find that I was so effeminate. What at school was merely thought to be feeble. I didn’t want to play games, I didn’t want to get hurt and this annoyed everybody very much. And would sometimes pretend that I was playing games and run round the field and try to get dirty. [laughter] And then on other days I would think, no this is nonsense. So I would lounge about saying, "what is football?" and so on. And it wasn’t until I left school and went out into the world that I thought, I must make up my mind. And then I decided that I would act out all the elements of my nature. The moment comes for everybody when he has to do deliberately what he used to do by mistake. And I suppose I realized this at about the age of 25. And from that moment onward it was all clear to me what I should do. I should adopt an appearance which told everybody what they seemed so desperately to want to know. Because if there are only two people left in the world alive, one thing will live with them, and that is the curiosity of the one about the sex life of the other. And so since this seemed to matter to everybody, to an extent, where because I wore makeup and dyed my hair, the crowds followed me through the streets, to the extent where you could not get the traffic through the street. Where you have to say that this is something they wanted to know. So, I made it possible for them to know instantly when they saw me exactly who and what I was.

JS: But Quentin Crisp is a lot more than those outward appearance factors?

JS: But Quentin Crisp is a lot more than those outward appearance factors?

QC: Yes. Now, of course, I’ve gone to the very edge of exhibitionism, [laughter] because inevitably the time comes when you find yourself moving from statement to protest. You find yourself doing things not to please yourself, but to annoy the neighbors. And you have to move back again. Because it is as absurd to try to offend the neighbors as it is to try to ingratiate yourself with them. What you have to do, as I see it, is to decide what you would be like if there were nobody else in the world. What would you do? If you had only yourself to consider. And once you’ve decided that, you’d do it and you’d be it and you’d stay with it for an entire lifetime. And then you have a core, you have some certitude inside yourself about the rightness of what you’re doing — in your own eyes.

JS: You’ve said that lifestyle for you is a religion.

QC: Lifestyle for me is, yes, it is a way of going on. So that it would cover everything. So that if a crisis were to arise I could say, is what I am doing or saying or wearing or thinking compatible with my lifestyle.

JS: I would imagine that it would be harder and harder for you and for many other people to find a sense of individuality. There is so much flamboyance, there is so much extravagance, there is so much theatricality, certainly in Los Angeles, the tinsel town of the world, I’m sure you’ve noted that walking down the "Boulevard" in Hollywood, that everybody is out to show off and to outdo their neighbor.

QC: Yes, this is true. And audiences have said to me, "What would you do if you found yourself outstyled?" Well, of course there’s no such thing. You don’t have to be more outrageous than other people. You don’t have to do anything about other people. You never make any comparison between yourself and others. You simply have to be more and more like yourself. And so of course, if you look into your soul and find that you’re ordinary, then ordinary you must be. But if possible, you must be so ordinary that you can imagine someone saying, come to my party and bring your humdrum friend, and that means you.

JS: [laughter] When you looked into your soul, when you searched the interior realm of your being, what did you find? Can you put that in words?

QC: I found that most of my mental characteristics were feminine, in spite of my body being masculine. And this is what worried everybody so much. My problem from the beginning was not a sexual problem, it is what Jan Morris calls a gender problem. It was a personality problem. And this worries people very little now. When the young people say to me, well what was it all about? And I say, well I did dye my hair. They say, and then? Because it makes no difference to them. But I come from a world where the difference between the sexes was so great that there were whole vocabularies which were suitable for men to use, no man in the middle classes of England, when I was young, would have said anything was "lovely" or "marvelous." There were the clothes you could wear. There were the movements you could make. Even the facial movements. No man ever rolled his eyes or smiled from ear to ear. Englishmen have very small facial movements. And so anything else was what my friends call "a dead giveaway." And you had to learn all this, or else do without it, you had to do the things which were natural to you and lump the consequences. But there are whole occupations which were "women’s work." My father wouldn’t have boiled a kettle because it was women’s work, and that meant degrading, which is a pretty terrible state of affairs. And I’m very pleased that even in England the sexes are more friendly now than they were in a time gone by. But still to this day, Englishmen do not really like the society of women.

JS: What if you’d been born into a different society, where equality was accepted and no one really was too concerned over appearance, over gender identification. A rather polymorphous perverse society. How would your life have been different if no one really cared whether you liked to sew or you liked to cook, whereas others did not?

QC: Oh, undoubtedly my personality would have been much less shrill. I would have been able, as you say, to do these things, without doing them in defiance of the world. And I would probably have been much more pleasant to know. [laugh] The trouble with a lot of people who have a personality problem, is not that people dislike the personalities they manifest, it’s that people get bored with the fact that they never talk about anything else. And this would not have applied to me if there had been no problem.

JS: I would imagine, though, if you stripped away all the antagonism, though, you would be left with, well, without a raison d'etre, perhaps.

JS: I would imagine, though, if you stripped away all the antagonism, though, you would be left with, well, without a raison d'etre, perhaps.

QC: Well, of course it did become the meaning of my life, that’s quite true. It became, in the beginning, a crusade. And I thought that I represented all the effeminate people in the world, which of course is rubbish. I merely represented myself. But it does give, did give in my case, an interest to my life that a lot of people may otherwise not have, to live through a single day was a kind of triumph.

JS: I think that would heighten your existence tremendously. In a way you’re fortunate, then.

QC: In a way I’m fortunate. All outsiders of any kind do have this fact that they bring to bear on every situation all they have, instead of merely taking it or leaving it, not really considering it very deeply. Every person you meet is a potential antagonist, and you spend your time making them over, working away at them, winning them over. Your life is one, long, tentative flirtation with the world.

JS: When you talk about style, I’m tempted to think of artifice, guise, masks. And I’m wondering whether you see these two concepts, these two ideas, as linked in any way.

QC: Oh, I think they are. What I mean by style is the opposite of this. Mr. Wilde said that in matters of great importance, it wasn’t sincerity that mattered, but style. And this to me means that he wasn’t truly a stylist. Because to me sincerity and style are the same thing. Just as in literature, style is not a question of raining down encrusted, bejeweled passages on rather banal material. Style in literature is removing all the words which don’t say what you really mean. And in the same way in style, in life, you have to find some way of leaving nothing of yourself to doubt, so that everybody does understand who you are, what you are, what you mean by what you say.

JS: So in other words you pare down everything that’s nonessential and you get to that core, the economy that expresses your inner essence, your style.

QC: That’s right.

JS: That’s not the way the word is usually used, I don’t think. I think it really –

QC: No, this is true. And this is a problem, and this I do have to explain in the theater. And I try to explain it in various ways.

JS: One of the things that I think is utterly wonderful about the message, and indeed you've come to America with a message, a message that isn't dissimilar from our recent fascination with "do your own thing" and "realize your potential" movement that many psychologists today have adhered to. But you say it differently, and one of the things that you said, and I heard really loud and clear is that what you are has to be more wonderful than what you do, which strips away and really attacks one of the foundations of American life which is so identified with doing as opposed to being. And you come across and you say, listen you need to pay attention to the being because those acts really is what counts.

QC: Yes, this is the essential part to me. You have to, if possible, get a profession where what you are is more important than what you do. And above all, what never matters is what you accumulate.

JS: Possessions.

QC: Possessions are a complete waste of time. You only surround yourself with those things which represent you.

JS: What do you have in your house that represents you, your little one room that you say you have?

QC: Well, in the one room I have nothing which isn't useful. There are no pictures, there are no ornaments of any kind, because I like to reduce my life to the essentials of staying alive.

JS: If you look at history, what fictional character, what historical character do you feel the most kinship to?

QC: Well, I've been asked that before and I can't think of any, though of course we all take, just as we take from fashion magazines things which we've always waited to see and then one day they turn up and we say, that's what I want, now I can buy it and I'll wear it for the rest of my life. So of course, when you meet people or when you see history you think, that's what I would like to do. And then you try to do it. So we are all learning from the world. It would be nonsense to say you sit with your eyes shut and your hands over your ears and think who you are. You must take something from the world. But I can't remember ever saying of any particular character that I longed to be them or I would have liked to have lived in their circumstances. When I was a child, uh — certainly the people that I was most interested in were the movie stars, particularly the great women movie stars. And there were more movie stars then, than there are now, because the world has got cross with the idea of stardom. And I'm asked sometimes what went wrong, why there are now no movie stars and no stage stars. And of course the answer is that you got rid of them.

QC: Well, I've been asked that before and I can't think of any, though of course we all take, just as we take from fashion magazines things which we've always waited to see and then one day they turn up and we say, that's what I want, now I can buy it and I'll wear it for the rest of my life. So of course, when you meet people or when you see history you think, that's what I would like to do. And then you try to do it. So we are all learning from the world. It would be nonsense to say you sit with your eyes shut and your hands over your ears and think who you are. You must take something from the world. But I can't remember ever saying of any particular character that I longed to be them or I would have liked to have lived in their circumstances. When I was a child, uh — certainly the people that I was most interested in were the movie stars, particularly the great women movie stars. And there were more movie stars then, than there are now, because the world has got cross with the idea of stardom. And I'm asked sometimes what went wrong, why there are now no movie stars and no stage stars. And of course the answer is that you got rid of them.

JS: We wanted a more democratic kind of process.

QC: That's right, you wanted the democratic process. And you were mistaken.

JS: We were mistaken, eh?

QC: Yes.

JS: What do you think we've lost?

QC: You've lost the thing which the movies were able to do that no other form of entertainment could do, which is to exploit physical style, physical idiom. Because you can see so much of movie stars. You can see them move their hands and their feet. You can see them move their eyebrows. Therefore you can see the way their bodies express themselves. Whereas you can't on the stage, everyone's a long way off. And you're sitting there with your opera glasses saying, oh she's sad because he's dead, but it's all a long way off. In fact, you're not quite sure and he gets up and you think, no he's not dead. Whereas in the movies you see it all, you see everything they think.

JS: I sense a preoccupation, I have to return to it, with the gesture, with mannerisms, with physical posture and gait. And I still am trying to find out, beyond that if I were to keep probing with my scalpel, my verbal scalpel, does the private Quentin Crisp differ, is there a private self beneath all this concern with appearance.

QC: No, there's none.

JS: There is none.

QC: There is none. What audiences see is all there is. They know me at the end of the evening as well as people who have known me for 50 years.

JS: They do. Just a bubble underneath all this?

QC: Yes.

JS: Just a nothingness, a core of nothingness beneath all this?

QC: There's only myself beneath it all. And everything I do and all the movements and all the phraseology, they are all only an expression of myself.

JS: Mark Twain once said that humor does not come from joy, but rather from sorrow. That the true humorist really has angst underneath the tongue in cheek kind of parley. Do you think that's true?

QC: Well, I think to some extent. Unlike wit, which is purely verbal, which is an arrangement of the words, humor consists of having at least two views of the same situation. Well, this already means that you will become diminished by humor, your self. Because as well as thinking, "I have been wronged," "these people have been unkind to me," you also have to see whether they were absolutely at their wit's end. To them, they may have been behaving in an extremely forbearing way — in treating you in the way that you consider outrageous. And it is these two views which make humor. It is seeing that while one person is saying, "I have been appallingly treated" another person is saying, "I did the very best I could, I was absolutely, I thought I was going to hit him but I only said, I think you'd better leave now."

JS: How does this relate to the material of the humorist, I'm not clear.

QC: Well, you see, you have to express, if possible, all the points of view that are possible about one situation. And this means that in a story, both points of view will be given. The person, the heroic saga of someone's life as seen from their own point of view will be described. And at the same time, the terrible fool that this person is making of himself in the eyes of others must also be described. This is the essence of humor. So as Mr. Twain said, at the same time that you are laughing, you are seeing yourself as absurd, because you see yourself from outside as well as from inside.

QC: Well, you see, you have to express, if possible, all the points of view that are possible about one situation. And this means that in a story, both points of view will be given. The person, the heroic saga of someone's life as seen from their own point of view will be described. And at the same time, the terrible fool that this person is making of himself in the eyes of others must also be described. This is the essence of humor. So as Mr. Twain said, at the same time that you are laughing, you are seeing yourself as absurd, because you see yourself from outside as well as from inside.

JS: That statement that you just made is reasonably straight on. A lot of the kinds of statements you come out with, however, during the course of spending an evening with you, are all tongue in cheek. And, sometimes when I was sitting and watching you I was wondering, "what would happen if he took his tongue out of his cheek?"

QC: Ah, I never say what I don't mean. It's only the way the things I expressed that seemed to other people to be a joke. Aphorisms are a waste of time if they don't express a truth. So that, whatever I say, all these quotes that appear in the papers, are an expression of what I really think. It’s only that the words have been fitted together so as to make a paradox or an aphorism. But nothing is really funny unless it is partly true.

JS: I see. So everything that I've heard you say I can essentially take at face value and just understand that you have a rather unique style of putting the words together.

QC: Yes.

JS: If a young person came to spend an evening with you, theatrically, they would have heard you say that cohabitation is a big mistake, that you find the nesting instinct in human beings a bit funny. You probably would have had a big chuckle if you'd watched people filing onto Noah's ark in the pattern, the dance of the twos. What if they take that at face value.

QC: Well, you see, there it is. It is the extreme statement of a truth. Of course people will always live in pairs. But they must be warned that it has its disadvantages. And when I say that the disadvantage is that if two people share a territory, they will be left with the things about which they disagree, this is true. The things that will stay with them, the things about which they don't remind themselves are, if they don't remind themselves they are things about which they disagree. What they talk about is the things about which they disagree. When someone comes to you and you say, how is your marriage going on? They don't give you a list of all the things about which they agree with their husbands. They say, "what do you think he's done now?" And so this is what people have to remember, that this will happen. Now, it may still be worth their while for various reasons. But what I say is what I mean, is that these are the dangers of sharing a territory, which would not exist if you cohabited sexually for a lifetime with somebody, but you lived in one street and he lived in the next street.

JS: Well, perhaps men and women thrive upon lack of harmony in their lives. Perhaps that's the reason they do marry, so that they can fight?

QC: Yes, this might be so. I would hate it, I must admit.

JS: You would, you've never lived with anybody?

QC: I've never lived with anybody. Because, for that very reason. Once I'd said to anyone, don't put your feet up there, then I would have to leave. That would be the end.

JS: [laughter]

QC: I couldn't live through having given way in that sense.

JS: Are you a romantic?

QC: I think originally I was, at least a dreamer, in the sense that when I was a child, I read the works of Ryder Haggard. I lived in that world in which everything was beautiful and all actions were heroic. Now, I don't think I'm by any means a cynic, but my view of life is more realistic, I think.

JS: What are some of those realistic truths that you've grasped, embraced?

QC: Well, when I say that, when I warn people of the dangers of sharing a territory, it won't all be cozy, I mean what I say. And when I warn outsiders not to adopt an exile's view of the rest of the world, not to imagine that because they are on the outside looking through the window, they must not imagine that the fireside racket is always cozy, is always permanent. And that the terrible news is, is that in there they are trying to get out. This is also true. I mean what I say. People who have a cozy settled life are forever saying, "if only something would happen." The people who are on the outside are saying, "if only I could get some peace." And this is something you have to settle for in life.

JS: What we're dealing, I think, with a state of affairs where people thrive, again, on being malcontents.

QC: I think inevitably, um, if you had a lifetime in which you always were given savory food, you would long for sweet food. It's not out of perversity, this is just a natural balance in your life, because the words "savory" and "sweet" only exist because you are the in the middle of them, you see. So therefore, if you want "love," there are times when you want your freedom. And if you are totally free, you long for the burden of these decisions to pass, if only there was someone here who would take this burden from me. But this is again because the words "freedom" and "burdens" — they only exist because you are in the middle.

JS: You start the evening in the theater by saying that you're here, there, to cure us of our freedom. And I, in my mind, thought, "OK, if he's here to cure us of our freedom, he wants to take on, and he thinks we need chains of some kind." I was wondering if you could spell out some of the chains that you have willingly and joyfully fettered yourself in?

QC: Yes, my appearance is one of them.

JS: It's a chain.

QC: It now never changes. Except in the tiniest detail. I have undertaken to be exactly like myself all the time. So, I've made up my mind, and I don't know, I've discarded any hankering to be somebody else, even for an hour. I have no occupations other than going round the world and saying what I think. And I have disciplined myself to do this, so there's never a time when I say, "no I'm absolutely worn out, I'm not going to do it". I will rise to whatever occasion demands that I go and explain myself and my views to other people. So I am living a life, in a way, that certain people would say, "well what a marvelous life, he now goes all over the world, he's taken hither and thither by air, he lives in expensive hotels." On the other hand, all my life is given to the world. I don't have a life, I have very few hours in which I'm doing anything except sleeping or being with the world. Now, this I like. But I mustn't ever complain that I have brought this state into being. I've done it myself and this is the life that I live.

QC: It now never changes. Except in the tiniest detail. I have undertaken to be exactly like myself all the time. So, I've made up my mind, and I don't know, I've discarded any hankering to be somebody else, even for an hour. I have no occupations other than going round the world and saying what I think. And I have disciplined myself to do this, so there's never a time when I say, "no I'm absolutely worn out, I'm not going to do it". I will rise to whatever occasion demands that I go and explain myself and my views to other people. So I am living a life, in a way, that certain people would say, "well what a marvelous life, he now goes all over the world, he's taken hither and thither by air, he lives in expensive hotels." On the other hand, all my life is given to the world. I don't have a life, I have very few hours in which I'm doing anything except sleeping or being with the world. Now, this I like. But I mustn't ever complain that I have brought this state into being. I've done it myself and this is the life that I live.

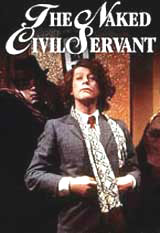

JS: So indeed you are, really, a public servant.

QC: So in a sense, I'm a public servant. As far as I can be.

JS: How do you relate to the concept of service?

QC: Well, that's one of the things that I regret. That what has disappeared altogether from the world is the will to serve. And whenever I've done any job that I've done, I've always thought, how can I do more? When I was a model in the art schools I used to say to the students, what shall it be, shall I climb up the wall? Shall I roll on the floor? Shall I take off all my clothes, some of my clothes, none of my clothes. Of course you never get any answer because they say they don't know. They have no ideas. But if they had, I would have carried them out. If I could have done. Because, as far as I'm concerned, the only way to make a job interesting is to do it more, not to do it less. And in England we now have a world ruled entirely by this grudgingness, this desire to get your wages raised by simply shouting instead of by saying, "if I did more would you pay me more?" I myself have never asked for more wages in all my life. And I have never earned more than 12 pounds a week over a long period, in the whole of my life. That's about $25. And yet I am here, neither embittered nor anxious. So all this screaming about one's wages is a complete waste of time.

JS: One last question. I sense that you feel that you're a realized being, and I want to know if that's true?

QC: I feel that what little I can do and say and be, I have now done and said and been.

JS: So you've made peace with yourself and the world, essentially?

QC: Yes.

JS: And Quentin Crisp has really made a reputation for himself. You pointed out in the theater to us that you're not famous, you're notorious. I think that's indeed true. In a universe where people are grappling with the question of identity, you've found an identity, you forged an identity, and those questions are laid at rest for you. I think that's really remarkable. I'd like to thank you for guesting with me. It's been a pleasure.

QC: Thank you.

JS: I'm Jessica Schuman for KPFK in Los Angeles.

JS: But Quentin Crisp is a lot more than those outward appearance factors?

JS: But Quentin Crisp is a lot more than those outward appearance factors?  JS: I would imagine, though, if you stripped away all the antagonism, though, you would be left with, well, without a raison d'etre, perhaps.

JS: I would imagine, though, if you stripped away all the antagonism, though, you would be left with, well, without a raison d'etre, perhaps.  QC: Well, I've been asked that before and I can't think of any, though of course we all take, just as we take from fashion magazines things which we've always waited to see and then one day they turn up and we say, that's what I want, now I can buy it and I'll wear it for the rest of my life. So of course, when you meet people or when you see history you think, that's what I would like to do. And then you try to do it. So we are all learning from the world. It would be nonsense to say you sit with your eyes shut and your hands over your ears and think who you are. You must take something from the world. But I can't remember ever saying of any particular character that I longed to be them or I would have liked to have lived in their circumstances. When I was a child, uh — certainly the people that I was most interested in were the movie stars, particularly the great women movie stars. And there were more movie stars then, than there are now, because the world has got cross with the idea of stardom. And I'm asked sometimes what went wrong, why there are now no movie stars and no stage stars. And of course the answer is that you got rid of them.

QC: Well, I've been asked that before and I can't think of any, though of course we all take, just as we take from fashion magazines things which we've always waited to see and then one day they turn up and we say, that's what I want, now I can buy it and I'll wear it for the rest of my life. So of course, when you meet people or when you see history you think, that's what I would like to do. And then you try to do it. So we are all learning from the world. It would be nonsense to say you sit with your eyes shut and your hands over your ears and think who you are. You must take something from the world. But I can't remember ever saying of any particular character that I longed to be them or I would have liked to have lived in their circumstances. When I was a child, uh — certainly the people that I was most interested in were the movie stars, particularly the great women movie stars. And there were more movie stars then, than there are now, because the world has got cross with the idea of stardom. And I'm asked sometimes what went wrong, why there are now no movie stars and no stage stars. And of course the answer is that you got rid of them. QC: Well, you see, you have to express, if possible, all the points of view that are possible about one situation. And this means that in a story, both points of view will be given. The person, the heroic saga of someone's life as seen from their own point of view will be described. And at the same time, the terrible fool that this person is making of himself in the eyes of others must also be described. This is the essence of humor. So as Mr. Twain said, at the same time that you are laughing, you are seeing yourself as absurd, because you see yourself from outside as well as from inside.

QC: Well, you see, you have to express, if possible, all the points of view that are possible about one situation. And this means that in a story, both points of view will be given. The person, the heroic saga of someone's life as seen from their own point of view will be described. And at the same time, the terrible fool that this person is making of himself in the eyes of others must also be described. This is the essence of humor. So as Mr. Twain said, at the same time that you are laughing, you are seeing yourself as absurd, because you see yourself from outside as well as from inside. QC: It now never changes. Except in the tiniest detail. I have undertaken to be exactly like myself all the time. So, I've made up my mind, and I don't know, I've discarded any hankering to be somebody else, even for an hour. I have no occupations other than going round the world and saying what I think. And I have disciplined myself to do this, so there's never a time when I say, "no I'm absolutely worn out, I'm not going to do it". I will rise to whatever occasion demands that I go and explain myself and my views to other people. So I am living a life, in a way, that certain people would say, "well what a marvelous life, he now goes all over the world, he's taken hither and thither by air, he lives in expensive hotels." On the other hand, all my life is given to the world. I don't have a life, I have very few hours in which I'm doing anything except sleeping or being with the world. Now, this I like. But I mustn't ever complain that I have brought this state into being. I've done it myself and this is the life that I live.

QC: It now never changes. Except in the tiniest detail. I have undertaken to be exactly like myself all the time. So, I've made up my mind, and I don't know, I've discarded any hankering to be somebody else, even for an hour. I have no occupations other than going round the world and saying what I think. And I have disciplined myself to do this, so there's never a time when I say, "no I'm absolutely worn out, I'm not going to do it". I will rise to whatever occasion demands that I go and explain myself and my views to other people. So I am living a life, in a way, that certain people would say, "well what a marvelous life, he now goes all over the world, he's taken hither and thither by air, he lives in expensive hotels." On the other hand, all my life is given to the world. I don't have a life, I have very few hours in which I'm doing anything except sleeping or being with the world. Now, this I like. But I mustn't ever complain that I have brought this state into being. I've done it myself and this is the life that I live.