TWO LIVES IN THE THEATRE:

Quentin Crisp and Spalding Gray

by Don Shewey

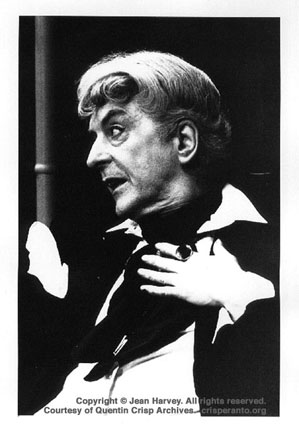

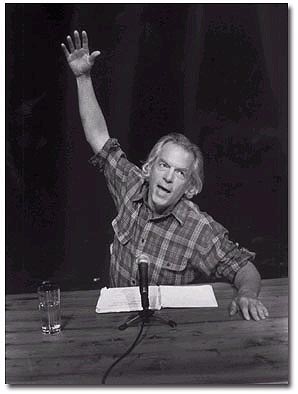

Quentin Crisp is a 70-year-old British eccentric with a name like an Evelyn Waugh character or an American breakfast cereal. His conversation distills thoughts into Oscar Wildean epigrams. Refusing to conform to a society in which he always felt alien, he has become, he says, "one of the stately homos of England." Spalding Gray is a 37-year-old New York actor. He grew up in Rhode Island, the middle son of a WASP family rich enough to have a summer place. He has worked in the theater since he was a teenager and has for several years been a member of Richard Schechner's experimental Performance Group. These two very different men are, in very different ways, engaged in the process of putting their life stories onstage — making blatantly autobiographical theater.

Of course, most modern art emanates from an autobiographical impulse. Yet, in even the most obvious examples — such as John Updike's tales of the Maple family, Frank O'Hara's "I-do-this-I-do-that" poems, Tennessee Williams's incessant re-creation of monster mothers and pure but damaged girls — self-portraiture is hidden behind characters, themes, invented plots. This way, the author's personal history can be used and re-used in endless variations, through an entire career. The peculiar thing about An Evening with Quentin Crisp, at New York's Players Theater Off Broadway, and Nayatt School, at the off Off Broadway Performing Garage, is that there is no pretense of disguising raw autobiographical materials as something else. It is even misleading to say that Crisp and Gray "play" themselves. They are themselves.

An Evening with Quentin Crisp is not a play, nor is it theater in the strictest sense. It is structured like a lecture — Crisp discourses for about an hour, then, after an intermission ("a pause and a good cry"), he takes questions from the audience. Practically speaking, An Evening is a promotional event meant to gauge interest in a musical version of Crisp's autobiography The Naked Civil Servant, which was written in 1968 and made into a British television play (starring John Hurt) in 1976. Its success has made this curious creature famous. Crisp had already made himself moderately notorious by parading through the streets of London in garish makeup, hennaed hair and high-heeled shoes, "not merely a self-confessed homosexual but a self-evident one." Most of his life has been a crusade to persuade a dubious public that "effeminacy exists in people who are in all other respects just like home." His book describes this outrageous, sometimes dangerous mission, and his show tells how he gave it style.

Style is a religion Crisp preaches with evangelical fervor. He defines it thus: start with your identity, a combination of your assets and what your friends mean when they discuss "the trouble with you"; polish that, and you have style. Style, Crisp says, is learning to do deliberately what one formerly did by mistake. This sounds like an entirely frivolous conceit, but Crisp is perfectly serious when he contends that we have too much freedom and that television, advertising, and affluence distract us from finding out who we really are. And, when he dismisses Russia as "a land without lipstick," there is a certain perspicacity beneath the camp witticism.

One's first response to Crisp's rap is to stand aloof and laugh, to chalk it all up to delusion, to dismiss him as foolish; applying his ridiculous philosophy would seem to mean spending one's life primping like a vain movie star. But some of what he proposes makes sense. The message is as scary as it is simple: be yourself. In other words, cultivate your differences, resist homogenization. Take responsibility for your life rather than relinquishing it to est, religion — or a Jim Jones. Crisp's reference to the People's Temple, coming on the heels of his discussion of style, has great power — for cults are the antithesis of personal style. Easing away from soberness, though, Crisp concedes that leaders of cults can have great style. "People ask me if Hitler had style, and I reply — of course. Why else is Germany a country of elderly people scratching their heads and saying, 'I don't know what came over me'?" The theory of style Crisp espouses, onstage as in life, is eminently debatable, but one must admit that it has its points.

Nayatt School is, to say the least, another kettle of fish. It is one of Three Places in Rhode Island, a trio of theater pieces composed over a period of four years by Spalding Gray and director Elizabeth LeCompte, with whom he lives. Sakonnet Point (named for the Gray family's summer residence) is an almost wordless evocation of childhood through a series of images. Rumstick Road is a semi-documentary voyage into the personality of Gray's mother, who, after her first nervous breakdown, had a vision of Christ and became a Christian Scientist and, after her second, committed suicide. Among its real materials, the piece uses tape recordings of awkward, ultimately inconclusive discussions between Gray (nicknamed "Spud") and his relatives, about his mother's death. Nayatt School, which completes the trilogy, takes from its predecessors various props and themes, especially childhood images and the mystery of Gray's mother's suicide. But it gets all mixed up with — of all things — T.S. Eliot's The Cocktail Party.

Nayatt School is, to say the least, another kettle of fish. It is one of Three Places in Rhode Island, a trio of theater pieces composed over a period of four years by Spalding Gray and director Elizabeth LeCompte, with whom he lives. Sakonnet Point (named for the Gray family's summer residence) is an almost wordless evocation of childhood through a series of images. Rumstick Road is a semi-documentary voyage into the personality of Gray's mother, who, after her first nervous breakdown, had a vision of Christ and became a Christian Scientist and, after her second, committed suicide. Among its real materials, the piece uses tape recordings of awkward, ultimately inconclusive discussions between Gray (nicknamed "Spud") and his relatives, about his mother's death. Nayatt School, which completes the trilogy, takes from its predecessors various props and themes, especially childhood images and the mystery of Gray's mother's suicide. But it gets all mixed up with — of all things — T.S. Eliot's The Cocktail Party.At the beginning of Nayatt School, Gray sits down at a long table. Like Quentin Crisp, he has a pitcher of water nearby, as well as a leather satchel and a record player. Gray begins to talk almost offhandedly about his acting career — shows he has been in, actors he knows, etc. — and his childhood. He explains that, because of a reading disability, he listened to spoken-word records rather than reading books; he also listened to the radio a lot and particularly relished horror-story programs. He then begins discussing The Cocktail Party, commenting at length on the Alec Guinness/Irene Worth recording of the play, from which he plays a brief snatch or two. As he does so, other people join him at the table. Gray asks one woman to join him in a reading of Eliot's scene between the psychiatrist Sir Henry Harcourt-Reilly and Celia Copplestone. During the reading, Gray occasionally stops to give the woman line-readings or to point out to the audience significant passages. Another man puts on a sad record, applies glycerine to his eyes, and "cries." Much is made of Celia's statement, "I should really like to think there's something wrong with me — because, if there isn't, then there's something wrong...with the world itself — and that's much more frightening!"

Gray's manner, calm at first, becomes more ominous and stylized until, at the end of the reading, when Celia decides to enter a sanatorium, Nayatt School goes haywire. Record players, records, and music seem to be everywhere. The actors leave the table and move to another playing space where they act out, in broad comic style, three scary sketches about a jealous husband, a breast-cancer examination, and a malignant chicken heart. Much craziness ensues, culminating in a bizarre enactment of The Cocktail Party's final scene (in which it is learned that Celia has gone to Africa as a missionary and has been crucified by cannibals) featuring children in four of the roles. Finally, Gray, another man, and a woman return to the long table, destroy record albums, take off their clothes, and gyrate grotesquely while squatting over record players. Something is wrong with this world, and it is frightening.

Even from the brief synopses I have given of these radically different productions, intriguing contradictions emerge with regard to autobiography and performance. Quentin Crisp's discourse on style is essentially a self-justification; he has looked back over a life mostly spent enduring and made endurance a virtue. Asked whether, given the chance, he would have lived his life differently, he seems puzzled: "It could not have happened any other way." Sad and deluded as he may seem, An Evening of Quentin Crisp is obviously the creative sum of his experience. Nayatt School, on the other hand, seems to indicate that nothing can be made from the past. Gray clearly associates Eliot's Celia Coplestone with his mothers; he sees in the character parallels to his mother's struggle to reconcile physical and spiritual life and her search for a beautiful vision. however, coming at the end of a trilogy director LeCompte has claimed is about "Spalding's love for the image of his mother, and his attempt to repossess her through his art," Nayatt School suggests that questions about the past, at least the ones Gray poses, have no answers and that to pursue them leads only to chaos and perhaps madness.

The other contradiction is this. Quentin Crisp has been a regular person all his life, and by staging his autobiography he has become — at least by dint of appearing nightly on a legitimate stage — an actor. Spalding Gray has been an actor all his life, and by using the details of his life story to create Three Places in Rhode Island, he has lifted the mask and become, almost unexpectedly, more of a person.

DON SHEWEY was born in Denver, Colorado, grew up in a trailer park on a dirt road in Waco, Texas, lived the peripatetic childhood of an Air Force brat, studied at Rice University and Boston University, and now lives in midtown Manhattan halfway between Trump Tower and Carnegie Hall. As a journalist and critic, he has published three books about theater and written articles for the New York Times, the Village Voice, Esquire, Rolling Stone, and other publications. He has chronicled his psycho-sexual-spiritual adventures in essays that have been included in several anthologies, including “The Politics of Manhood,” “Best Gay Erotica 2000,” and “The Young and the Hung.”

Quentin Crisp photograph copyright © by Jean Harvey. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Spalding Gray photograph may be subject to copyright. Used without permission.

Text copyright © by Don Shewey. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

This essay first appeared in the Boston Phoenix, February 1979.

Site Copyright © 1999–2008 by the Quentin Crisp Archives

All rights reserved.

Spalding Gray photograph may be subject to copyright. Used without permission.

Text copyright © by Don Shewey. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

This essay first appeared in the Boston Phoenix, February 1979.

Site Copyright © 1999–2008 by the Quentin Crisp Archives

All rights reserved.